9 January 2002

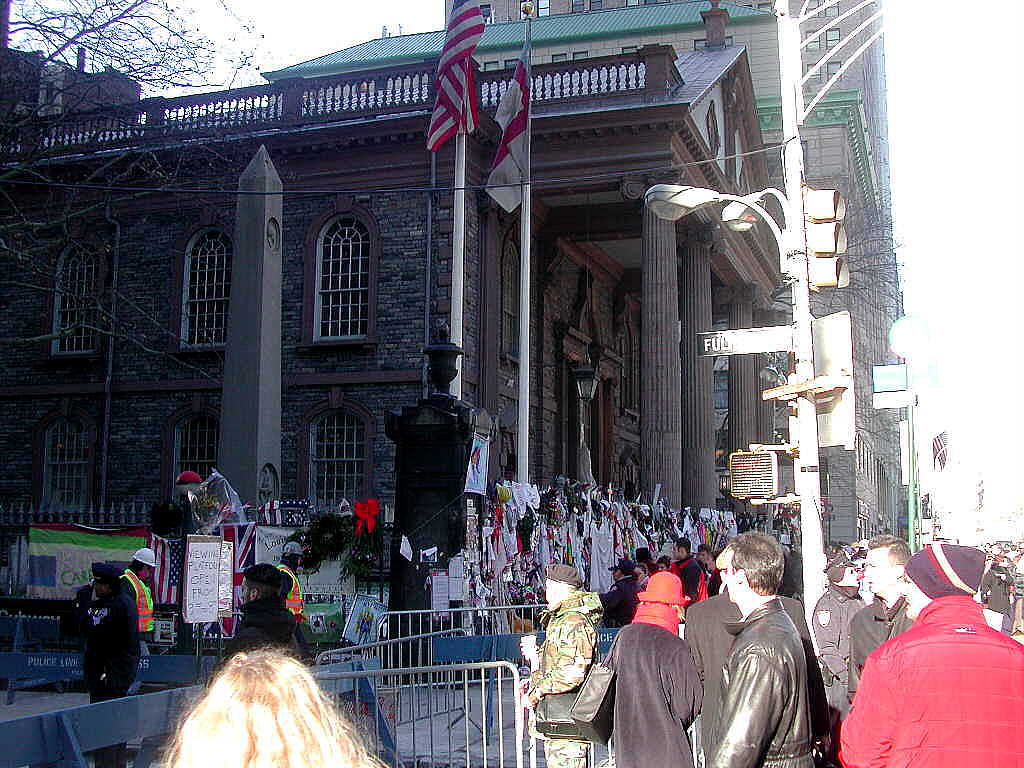

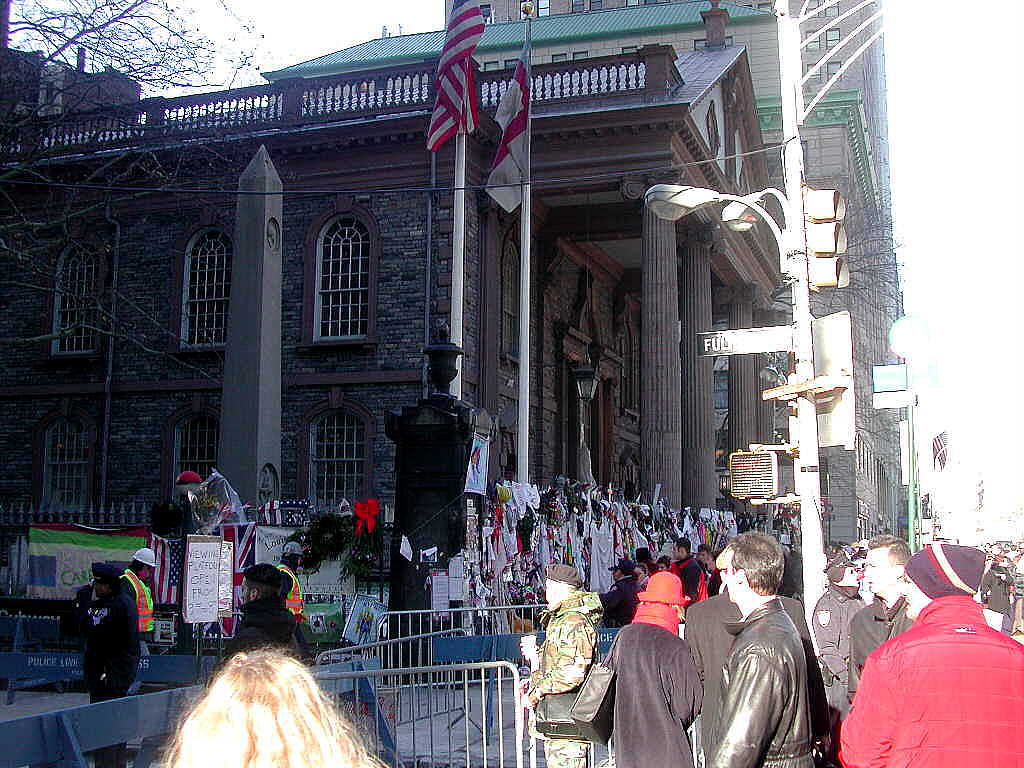

This provides photographs and news reports on the first of four viewing platforms to be constructed at the WTC site. The first is located adjacent to St. Paul's Chapel, at Broadway and Fulton Streets.

The platform is the first constructed visitor accommodation at the site, which has become the premier attraction of New York City. Dozens of informal shrines to victims and rescuers have been made by visitors around the perimeter of the sites, with one of the largest in front of St. Paul's Chapel.

The platform ensemble consists of up and down ramps separated by a vertical divider, with viewing platform overlooking the site. Visitors are encouraged to write messages on the bare wood surfaces. The platform was designed and built by contributed services, labor and materials, as described in reports below.

Photographs by Cryptome, January 8, 2002

Just above the heads of viewers on the platform is gap between buildings from which the photos below were taken from the opposite side of the WTC site. See artists' view of the platform below.

Following views are looking at the platform from the opposite side of the

WTC site, with St. Paul's Chapel steeple in the lower center behind a row

of trees along Church Street, the eastern perimeter of WTC. Viewers on the

platform are just above the police scooter:

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/22/arts/22PLAT.html

December 22, 2001

AN APPRAISAL

By HERBERT MUSCHAMP

Transparency — unobstructed vision — is the solid virtue that will hold aloft a set of public viewing platforms on the perimeter of ground zero. Construction has begun on the first of four nearly identical platforms now proposed. The temporary structure is on Fulton Street, between Church Street and Broadway, just south of St. Paul Chapel, and it is to be completed by Friday.

Designed by an independent group of architects with support from a diverse group of city officials, union leaders and private donors, the viewing platforms are also notable for the disarming ease with which they have glided through unusually dense thickets of red tape. A city still in shock from September's terrorist attack has managed to create a quiet, dignified approach to what is now historic ground.

The platforms, a grass roots initiative, were designed by four of the city's most highly respected architects: David Rockwell (Rockwell Group), Kevin Kennon, Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio (Diller & Scofidio). Major support for the project was extended by Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani and the heads of two city agencies, Christyne Lategano-Nicholas, of NYC & Company, the tourist and convention bureau; and Richard Sheirer of the Office of Emergency Management.

Built of exposed metal scaffolding and plywood planks, the platforms are visually neutral. They are not intended to be a memorial. Nonetheless, the design recalls an inverted version of Maya Lin's understated Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. U-shaped in plan, the platforms will be inserted like plugs into streets running perpendicular to the 16-acre site.

Two long, shallow plywood ramps, one for entering, the other for leaving, are attached to the platforms, which are 13 feet above ground. The ramps are 15 feet wide and 300 feet long, and visitors climbing them will gain a heightened awareness of their body weight, a physical metaphor for the gravity of the occasion. The narrow incline should also evoke a ceremonial procession. A plain birchwood wall, set between the ramps, is for posting photographs, writings and other expressions of memory, tribute and grief from visitors.

The station under construction will be entered from the Broadway end of the ramp on Fulton Street. The platform is to be 30 by 50 feet. An estimated 300 to 400 people can gather on the platform at a time. The entire structure will support more than 1,000 visitors at a time.

This project is unaffiliated with the professional groups already organized to prepare a coordinated response by New York architects to the terrorist attack. Materials, labor, design and engineering services were donated. Focus Lighting and the Atlantic-Heydt Corporation, a Queens hoisting and scaffolding concern, led the project's realization, which also relied on assistance from the many city departments overseeing the site.

The Alliance for Downtown New York, a business improvement district, will maintain the structures. Larry A. Silverstein, who acquired the lease on the World Trade Center last summer, has donated $100,000 to defray additional expenses for building the first platform. The architects have established a nonprofit organization, the WTC Platform Foundation, to raise the money to complete all four.

If feelings could be weighed, even rows of solid steel columns would not suffice to hold them up. The project is as emotionally charged as its design is simple. Though television has familiarized the world with ground zero, an unmediated encounter with the site is still overwhelming. The experience includes more than the sight of wreckage. No less moving are the placards, signatures, snapshots, writings, flags and other signs of personal loss.

For three months no property in the world has been subject to greater pressure from public attention. It has even become a contested site. Surviving spouses, children, other family members, friends, uniformed officers, co-workers, public officials, downtown neighbors, ordinary citizens, journalists, real estate developers, architects: all have a right to be here, though their motives sometimes conflict.

Since Sept. 11, many architects and artists have put forth unsolicited proposals for ground zero. Some of them have organized to develop coherent plans for the future of the financial district. With a new mayor about to take office and a redevelopment agency now in place, the city has moved closer to that future. There is now a clearer sense that decisions will be made.

New buildings will or won't rise at ground zero. The financial center will or will not be induced to hold. Architecture and public spaces will be modeled after Battery Park City or after a more progressive vision of the contemporary city. Suspense will dissipate.

Given all these pressures, the appearance of the platforms could stir controversy. A decision has been made: one project is proceeding, others will not. The matter was not put to a referendum. No design competition was held. Issues of process and accountability were suspended. But this project emerged from a process of its own. Initiative, thoughtfulness, pragmatism and stealth were among its key components.

Most of the visions proposed by architects fell into one of two extremes. The bulk of them were personal fantasies projected onto the site with scant thought of realization. At the other extreme were ideas developed by the professional groups, like the American Institute of Architects, the Real Estate Board of New York, and the New York City Partnership. At one extreme, designers transmitted into a void. The other extreme is the void.

The professional groups were unable to grasp the basic priorities. The most prominent of these groups, the N.Y.C. Rebuild Infrastructure Task Force, had its eyes set on the hyperinflated agenda suggested by its title. The terrorist attack, while earth- shattering, produced no need to rebuild New York or its infrastructure.

Within weeks of the attack this group had created a privatized bureaucracy of its own. Its agenda was often mystifying, contradictory and self-serving. Immediate needs for public access and transportation became linked to sugar plum visions of new office towers and rail lines. Too much effort went into supporting the idea that a memorial and an office park could be agreeably accommodated on one site. Not enough effort was directed at examining that premise and others.

The viewing platform project emerged from dissatisfaction with this professionalized status quo. Weekend crowds had established the need to provide public access to the site. A design was needed to serve the need. It had to be easy and cheap, sturdy, and flexible. It had to come in without arousing opposition and with the mayor's blessing. It didn't have to deal with complexities of meaning.

But the design does hold meaning. It embodies stoic principles. It treats the need for design as a reduction to essentials. The result has substance. Stop the mystification, the grandiosity, the use of architecture to disconnect our history from ourselves. Give the city back. These ideas deserve to outlive the limited duration of the platforms themselves.

In fact, a potential parallel exists between this design and the so-called interim plan that was adopted for 42nd Street in 1992 after the collapse of a plan to build four nearly identical office towers on Times Square. Emphasizing diversity, communications and media spectacle instead of uniform corporate gigantism, the interim plan guided Times Square toward its current identity as a meeting ground for the producers and consumers of popular culture.

The temporary viewing platforms could perform a similarly pivotal role in reconceptualizing the identity of lower Manhattan. Other choices will eventually be made, decisions that will affect the cityscape for generations. Our builders could choose the no-risk option represented by Battery Park City: Ye Olde New York retrofitted with pseudo-progressive public art. Or just when the value of risk-taking itself is in jeopardy, they could look for new ways to interpret the city to itself.

There is no need to rush. What we're looking at is a process of taking stock that has barely commenced. Renzo Piano, architect of the future headquarters of The New York Times, told a reporter recently that the architects who could design well for ground zero are now only 4 or 5 years old. It takes time to achieve transparency where meaning is concerned.

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/03/garden/03ROCK.html

January 3, 2002

By JOHN LELAND

As you walk up the 300-foot ramp to the viewing platform at ground zero, the wreckage of the towers is blocked from sight. Instead, the view is of the weathered graveyard behind St. Paul's Chapel. It can take an hour or more in a cold line to reach this point, and this first glimpse, of primitive death commemorated in battered limestone, is a sobering prelude to the 16-acre pit to come.

The voices in the crowd fall silent here; the stones could whistle in the wind.

The viewing platform, which opened Sunday and has attracted huge crowds of visitors, is the first architectural response built after the attacks of Sept. 11. Designed by four of the city's best-known architects, and made possible by what the architects describe as extraordinary support from city agencies and private contractors, the platform offers a bold proposal about how New York might begin its renewal.

"This was a very emotional project for everyone involved," said Richard Sheirer, commissioner of the Office of Emergency Management, who helped marshal city agencies behind the construction.

The architects are David Rockwell of the Rockwell Group, known for his stylish designs for restaurants and boutique hotels; Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio of Diller & Scofidio, whose recent work includes the sleek Brasserie restaurant in the Seagram Building; and Kevin Kennon, who recently left the firm of Kohn Pedersen Fox.

From such conspicuous names, the design itself could not be more elemental. Rising about 16 feet over Church Street at Fulton Street, it is a 30-foot-wide deck of unfinished wooden planks supported by steel scaffolding. By Monday morning, visitors had filled the wooden guardrails with scrawled tributes to the lives lost in the attack. "We tried to exercise as much restraint as possible," said Mr. Kennon, who lives downtown on Hudson Street and saw the collapse of the towers from his home. "It was important that there be no ornament whatsoever. We thought that would be inappropriate."

The main thrust, he said, was that the design impose "as few filters as possible" on the viewing experience. "We didn't want the platform itself to be a memorial."

The visitors' graffiti is part of the design, Mr. Rockwell said. "We wanted people to take something from it, but also leave something." He added that the planks can be easily replaced to make room for more tributes.

The platform is one of four that the group has proposed for the site. The other three await only funding, Mr. Sheirer said.

The idea to build a viewing platform began shortly after Sept. 11. In the aftermath of the attacks, Mr. Scofidio said, architects around the city were hastily proposing monuments or ambitious plans for rebuilding on the site. "We were shocked that it was happening so soon," he said. "People needed time to process intelligently what had happened. Our comment to a reporter at the time was, `Don't erase the erasure.' "

The scale of destruction wrought by the attacks had left many architects questioning the relevance of their work, Mr. Rockwell said. After a meeting with Mr. Kennon, the two agreed that it was important to build something — some architectural gesture of renewal — as quickly and efficiently as possible.

In late September, the two met with Cristyne L. Nicholas, president of NYC & Company, the tourist and convention bureau, to discuss ways in which they might collaborate with the city. The Port Authority had already built a small platform for families of victims. The group decided on a series of larger platforms for the general public. Ms. Nicholas brought the architects to one of Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani's morning staff meetings.

Mr. Sheirer spoke with victims' families, who "were concerned about people coming here, especially taking pictures," he said. "We make sure we tell people that this is a burial ground, not a tourist site."

The architects arranged a bridge loan of $175,000 from Norman Lear, the television producer, and set up a foundation to solicit donations. They have raised $360,000, Mr. Rockwell said, including $100,000 from Larry Silverstein, the developer who holds the lease on the World Trade Center.

Atlantic-Heydt, one of the largest providers of scaffolding in New York, lent building materials at no cost, and offered its labor at discount. The Forest Electric Corporation did the wiring, about 200 man- hours' worth, at no charge. Both contractors worked through Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. "We lost five individuals — members of our family, really — in the attacks," said Howard Hirsch, president of Forest Electric. "It was important that we do whatever we could."

A project like a viewing deck would normally require months of city paperwork, said Pat Crosbie, a project manager of Atlantic-Heydt. But with the mayor's office lending support, city agencies cleared the way in what all involved described as unprecedented speed. "All you had to do was make one phone call, and they'd walk you through," said Peter Michel, an assistant vice president of Forest Electric. The scaffolding and deck were built in two weeks.

Mr. Rockwell said he hoped the spirit of public and private collaboration would continue to shape the renewal process, even after the viewing deck goes down at some undetermined date.

The platform, which is officially open from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m., has drawn huge crowds, though police officers have let viewers in before 9 with little wait. The visitors first pass a sprawling impromptu memorial in front of St. Paul's Chapel, then take the slow walk past the graveyard before reaching the deck.

On the morning of New Year's Day, Beverly Heafner, 66, who was visiting from Suffolk, Va., said she had never waited as long for anything in her life. But she had no complaints about the wait or the chill. "I tell you what," she said. "I was freezing cold. But as soon as I saw the memorial, it warmed me up."

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/national/AP-Attacks-Platforms.html

January 8, 2002

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 10:47 p.m. ET

NEW YORK (AP) -- The line of people solemnly waiting outside in the cold to see the ruins of the World Trade Center is frequently so long that the city has decided to issue tickets to the viewing platform.

The free tickets would allow up to 250 people on the platform for a half hour at a time.

``There were just too many people who couldn't get on the platform. They were waiting shivering in the cold,'' Mayor Michael Bloomberg said. ``We're just trying to do something to make it easier for people who are trying to pay their respects.''

The tickets will be available at the South Street Seaport Museum's ticket booth, about seven blocks from the trade center site, officials said. Tickets will be required beginning Wednesday.

The 13-foot-high wooden viewing platform, which is the first of a planned four, opened on Dec. 30. Despite bitter cold in recent weeks, thousands of people line up every day and wait up to three hours to climb onto the platform.

There have been concerns that the platforms will transform what should be hallowed ground into a tourist attraction. But Stephen White, who waited in line to enter the platform Tuesday evening, disagreed.

``I don't see it as a tourist site,'' the West Kingston, R.I., resident said. ``It has a tourist aspect, but that's not the point. We're here to come and pay our respects and go home.''

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/09/nyregion/09VIEW.html

January 9, 2002

By THE NEW YORK TIMES

To enable people to see the site where the World Trade Center once stood without having to stand in line for hours in the cold, the city will begin offering free tickets to the public viewing stand for 15-minute periods today.

The viewing stand, an elevated wooden platform on Fulton Street between Broadway and Church Street, has attracted thousands of people since it opened on Dec. 30.

Under the arrangement, first reported in The Daily News, tickets will be stamped with a time for visiting. They will be available at the South Street Seaport Museum and issued for the afternoon of the same day, or the morning of the next day. The platform is open daily from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m.

"There were just too many people that couldn't get on the platform, they were standing there, shivering cold," Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg said yesterday. "This way they don't have to wait."

"When it's their time they can walk right up on the platform, pay their respects for the 15 minutes, and leave."

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/09/nyregion/09PROF.html

January 9, 2002

PUBLIC LIVES

By ROBIN FINN

The architect about town David Rockwell, designer of Nobu, the Monkey Bar and other culinary haunts favored by the slinky set, is just back from a private luncheon aboard the Queen Elizabeth 2 honoring his celebrity-chef buddies who convened at ground zero to turn out comfort food for rescue workers in the grim days after Sept. 11.

Lunch is nice enough, but his inner critic cannot resist a tsk tsk over the ship's décor: he gives his shaggy-dog haircut a shake and wonders aloud if it would be rude to call it dowdy. Never mind. It is not among his 20 projects, some continuing, some dormant, like the futuristic Singapore airport, with its internal aviary. Anyway, he despises ventriloquists, buffets, and all things cruise related. A city slicker who glibly calls his charcoal shirt and black jeans the closest thing he owns to a leisure suit, he cannot fathom being stranded, voluntarily, on an ocean.

He would much rather be stranded downtown. Mr. Rockwell, 45 and gym thin, is no celebrity chef (though he does wangle their secret recipes), but he volunteered at the disaster site, too: first on KP duty, assisting friends like Drew Nieporent, then last month serving up his vocational specialty, the creation of something from nothing — in this case with nothing more than planks, plywood, and scaffolding, most of it donated, because this was intended as a civic architectural gesture that would not cost New York City a dime.

Unlike his restaurant interiors, his beaded two-million-square-foot addition to the Mohegan Sun Casino in Uncasville, Conn., the Kodak Theater in Hollywood, which doubles as the site of the Academy Awards, and his witty theater sets, this project does not glow or feature a sweeping staircase, though it does have a ramp. It also has a humble relevance, he thinks, and after Sept. 11, relevance was something that preoccupied him.

"I was worried about how I could go back to work and have any relevance in making places if making places was largely about pleasure, which is kind of what we do here," he says, gesturing toward his Rockwell Group design staff of 90 — he refers to them as family — at 5 Union Square West. Then came the epiphany. "The act of creation is what we do. That's the statement against destruction."

So Mr. Rockwell, in collaboration with three other architects — Elizabeth Diller, Ricardo Scofidio and Kevin Kennon — conceived a construction project at ground zero, four viewing platforms whose purpose is to bring the public face to face with the devastation. Bearing witness, says Mr. Rockwell, who watched the first tower crumple from his office roof, then ran home to his wife and son at their Vestry Street loft as the second tower vanished, is what the project is all about. The first platform opened on Dec. 30; he hopes to finish two more next month.

"There are thousands of reasons why people want to get close to ground zero, ranging from ones we love to ones we would not love," he says. "But to be there and have that direct experience is, I think, startlingly powerful. To see the scars, as opposed to talking about what the future should be. Post-Sept. 11, there were all these major visions coming from the design community about what should happen there, whereas I couldn't begin to muster up anything."

He remains undecided about what, beyond turning a portion into park land, should happen at the site, insisting that redevelopment should evolve "from a conversation about why we choose to live in cities, and some of those reasons aren't office space." As for replicating the towers? "I think that's an insane line of reasoning."

A child of flux, Mr. Rockwell was born in Chicago, raised on the Jersey Shore until he was 10, and then relocated to Guadalajara, Mexico, for his stepfather's retirement. He lost his father when he was 2, and at 15 lost his mother, a vaudeville dancer before she had five sons.

He was the baby of a close-knit brood that staged summer theatrical productions during boyhood, but after his mother's death, "the baby had to get functional," he says. "I was sort of brought up in an environment of things not being in my control, of losing people, of the family moving. It left me with a feeling that having control of the big things in life is just so — uncontrollable. It's kind of a God-is-in-the-details thing." Hence his tendency to be "an obsessive perfectionist" even in the kitchen. And an optimist, "because I think it's the most intelligent choice."

His ambitions of being a concert pianist were cured by his first recital: "not fun." At Syracuse University, he majored in architecture but nearly dropped out after the first assignment when, in the time it took him to draw his sandal, a classmate sketched the entire campus. He pondered switching majors but was rebuffed by his professor. "He said the fact that I knew nothing about architecture meant I had less to unlearn."

In New York, Mr. Rockwell talked his way into a job as a theatrical lighting assistant to Roger Morgan after seeing "Dracula" on Broadway, then did a restaurant project at Sushi Zen on 46th Street that won a design award. And won him notice. The sushi bar was shaped like a lightning bolt; one wall was a silk mural designed to be edge-lit by neon fixtures the owners could not afford, so rather than scrap a beautiful detail, Mr. Rockwell borrowed the money and lent it to them.

It was worth it.